The word “Bollywood” is practically synonymous with bright lights, grand gestures, and picture-perfect endings. For millions, it’s a dreamland where the good guys always win, love conquers all, and tradition blends effortlessly with modernity. It’s uplifting — but also deeply escapist. For many South Asians in the diaspora, Bollywood movies are a comforting reminder of “home” — a place where familial bonds, colorful festivals, and communal gatherings play out in all their cinematic glory.

Yet, is this the South Asia we know? In reality, the Bollywood representation often leans towards a glitzy portrayal of urban India, occasionally dabbling in the rural landscapes. The diversity and vastness of South Asian experiences are seldom fully represented. The “Bollywood” version of South Asia is filtered through layers of glamor and melodrama, often disregarding the nuance, complexity, and sometimes even the harsh truths of South Asian societies.

One of Bollywood’s strengths, and arguably its weaknesses, is its ability to shape perceptions. For the uninitiated or those unfamiliar with South Asian culture, Bollywood can become the main reference point. In the diaspora, especially among younger generations of South Asians, Bollywood helps to bridge the gap between their parents’ heritage and the new culture they are growing up in. The catchy songs, relatable family dramas, and cultural festivals allow them to stay connected to their roots, to feel a little more “Indian,” “Pakistani,” “Bangladeshi,” or simply “South Asian.”

However, Bollywood has also been criticized for reinforcing stereotypes, especially those that exoticize and oversimplify South Asian culture for a global audience. The portrayal of women as either the perfect “bahu” (daughter-in-law) or the rebellious figure, often dressed in revealing attire, presents a problematic binary. The cultural diversity within India and across South Asia — languages, traditions, religions – is often overlooked, with “Indian culture” portrayed as homogenous. Even within India, the regional films of Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and others offer narratives far more diverse than mainstream Bollywood’s simplified narratives.

Over the years, Bollywood has tackled social issues ranging from poverty to caste discrimination, mental health and more. Films like Pink (2016), Article 15 (2019), and My Brother…Nikhil (2005) have addressed crucial social issues, earning critical acclaim for challenging conventional thinking. These movies have opened dialogues and contributed positively to raising awareness within India and among the global diaspora.

But this too can be a double-edged sword. Bollywood’s treatment of social issues can sometimes be shallow or overly dramatic, simplifying real-world struggles. For instance, when caste discrimination is addressed, it’s often through the lens of a privileged character who becomes the “savior,” which, while well-intentioned, can reduce complex societal issues to simplistic narratives.

Bollywood’s Hindi-language hegemony is another topic of contention in the broader South Asian context. While Bollywood is synonymous with Indian cinema internationally, it often sidelines regional Indian languages and films, reinforcing Hindi as the dominant cultural language of South Asia. This representation can alienate non-Hindi speakers both within India and the wider diaspora, as it implies that Hindi-speaking, North Indian culture represents all of India and by extension, South Asia.

Additionally, Bollywood’s success has sometimes overshadowed the film industries of neighboring countries like Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, each of which has its own vibrant cinema with distinct cultural narratives. For the South Asian diaspora, this might mean that Bollywood is often their only cinematic reference for “South Asia,” inadvertently limiting their exposure to the region’s diversity.

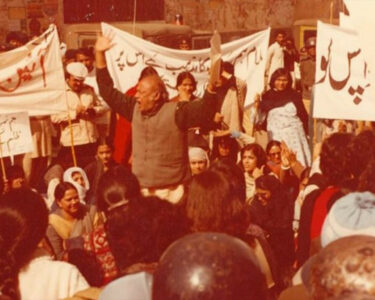

Bollywood’s reach isn’t just limited to culture; it has a strong political influence too. Over the years, Indian cinema has taken on subtle — and sometimes overt — political messaging. There have been films that celebrate Indian nationalism, support military action, and even create certain political narratives, especially in recent years.

For South Asians living abroad, these films can create an emotional but simplified notion of patriotism, often leaning into binaries like “us vs. them.”

This is further complicated by Bollywood’s depiction of neighboring countries, often painting Pakistan, for instance, in a negative light. While such portrayals might rally domestic audiences, they can alienate South Asians from these regions or foster stereotypes within the diaspora communities.

With Netflix, Amazon Prime, and other streaming services making Bollywood films more accessible than ever, Bollywood’s influence is now global. South Asian cinema has a unique opportunity to reshape and redefine the way the world views its identity. Bollywood’s worldwide platform means it has a responsibility to tell stories that do justice to the complexity of South Asian identity. By leaning into nuanced, authentic portrayals and moving beyond clichés, Bollywood has the potential to educate as well as entertain.

The landscape of South Asian cinema is rapidly changing, with regional films gaining international recognition and digital platforms providing alternative narratives. Audiences are beginning to seek more diverse, grounded stories that reflect the realities of modern South Asia — and not just in India. Movies like The Lunchbox and Masaan broke away from the Bollywood mold, focusing on everyday characters and raw, unpolished narratives. These stories resonate not just because they’re “South Asian,” but because they are genuinely human.

In an increasingly connected world, Bollywood’s impact on South Asian identity will continue to evolve. With its massive influence, Bollywood has the chance to move beyond the glitzy dream world and embrace a deeper storytelling tradition, one that genuinely reflects the hopes, challenges, and intricacies of South Asia. In doing so, it will not only serve as an anchor for the diaspora but also present a more genuine picture of South Asian culture to the world.